Abrego et alia 2017. Fungal Ecology, 27: 168–174. Understanding the distribution of wood-inhabiting fungi in European beech reserves from species-specific habitat models.

Afyon et alia 2004. Turkish Journal of Botany, 28: 351–360. Macrofungi of Sinop Province.

Afyon et alia 2009. Mycotaxon, 93: 319–322. A study of wood decaying macrofungi of the western Black Sea Region, Turkey.

Ahmad et al. 1997. Fungi of Pakistan.(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Aho & Filip 1982. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 12(3): 705–708. Incidence of wounding and Echinodontium tinctorium infection in advanced white fir regeneration.

(This citation appears to be erroneous.)

ALA = Atlas of Living Australia [https://www.ala.org.au/] Link confirmed 17 Mar. 2019.]

Albee-Scott 2007. Mycological Research, 111(6): 653–662. The phylogenetic placement of the Leucogastrales, including Mycolevis siccigleba (Cribbeaceae), in the Albatrellaceae using morphological and molecular data.

Alfieri et alia 1984. Florida Dept. Agric. and Consumer Serv., Div. Plant Ind. Bull. 11. Index of Plant Diseases in Florida (Revised).

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Allen et alia 1996 & 2007. Common Tree Diseases of British Columbia, 38–39. Heart rots: Yellow pitted rot. (Hericium abietis).

Anonymous 1960. USDA Agricultural Handbook, 165: 1–531. Index of Plant Diseases in the United States.

Anonymous 1964. Diseases of widely planted forest trees. From an FAO-UN symposium. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

(From USDA ARS GRIN; Not presently accessible.)

Anonymous 2014. USDA, Forest Service, Alaska Division, RG-209. Mushrooms of the National Forests in Alaska.

Arnolds 2001. In Moore et alia Fungal Conservation. Issues and Solutions. pages 64–80. The future of fungi in Europe: threats, conservation and management. (Digital version was in 2008.)

Astapenko 1990 [as Астапенко, В.В.]. Консортивные связи дереворазрушающих грибов в Среднем Приангарье [Symbiotic relations of wood-destroying fungi in the middle Angara river region]. Микология и Фитопатология [Mycology & Phytopathology] 24(4): 289–298.

(From Cybertruffle 2016. Not presently accessible.)

Astapenko & Kutafyeva 1990 [as Астапенко, В.В.; Кутафьева, Н.П.]. Консортивные связи макромицетов с видами рода Betula L. [Symbiotic relationships of larger fungi with species of Betula L.]. Микология и Фитопатология [Mycology & Phytopathology] 24(1): 3–9.

(From Cybertruffle 2016. Not presently accessible.)

ATCC product information, data gleaned from within individual entries at http://www.atcc.org/en/Products/Cells_and_Microorganisms/Fungi_and_Yeast/Fungi_and_Yeast_Alphanumeric.aspx [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Atila et alia 2018. Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology & Food Sciences, 7 (5) 532–536. Genetic Diversity of Hericium isolates by ISSRR and SRAP Markers.

Atlas of Living Australia website. Hericium reported from Australia [https://biocache.ala.org.au/occurrences/search?taxa=Hericium] and images [https://bie.ala.org.au/species/2ec3db20-d8b2-4ea8-b0e2-b38e7b09507f#gallery] [Links confirmed 17 March 2019]

Balfour-Browne 1968. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Botany, 4: 7–141. Fungi of recent Nepal expeditions.

Banker 1906. Memoirs of the Torrey Botanical Club, 12(2): 99–192. A contribution to a revision of the North American Hydnaceae.

Basham 1958. Canadian Journal of Botany, 36: 491–505. Decay of trembling aspen.

Berkeley 1860. Outlines of British Fungology, Vol. 2. pages 257–261. Hydnum.

Berry 1969. USDA, Forest Service, Research paper NE-126, Decay in the Upland Oak Stands of Kentucky.

Berry & Beaton 1972. USDA, Forest Service, Report NE-242, Decay in Oak in the Central Hardwood Region.

Berry & Lombard 1978. Forest Service Research Paper NE-413, Basidiomycetes Associated with Decay of Living Oak Trees.

Binion et alia 2008. Macrofungi associated with oaks of eastern North America.

(From Glaeser & Smith 2013. Not presently accessible.)

BCRC = Bioresource Collection and Research Center; Taiwan Fungal Flora Knowledge [http://www.bcrc.firdi.org.tw/fungi/index.jsp] [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Bisko et alia 2016. IBK Mushroom Culture Collection.

Boddy et alia 2011. Fungal Ecology, 4: 163–173. Ecology of Hericium cirrhatum, H. coralloides, and H. erinaceus in the UK.

Bondartseva et alia 1998. Folia Cryptogamica Estonica, 33: 19—24. Aphyllophoroid fungi of old and primeval forests in the Kotavaara site of North Karelian biosphere reserve.

Boudier 1905. Icones mycologicae ou Iconographie des champignons de France principalement Discomycetes, Vol. 1, plate 166; Vol. 4, page 85.

Bourdot & Galzin 1927. Hymènomycètes de France, pages 452—454. Dryodon.

BPI n/a. National Fungus Collections. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Brambilla & Sutton 1969. Host Index of Species Deposited in the Mycological Herbarium (WINF/M) of the Forest Research Laboratory, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Bresadola 1906. I Funghi Mangerecci e velenosi dell Europa Media, vol. 2, 112–113.

Buckland et alia 1949. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 27: 312–331. Studies in forest pathology. VII. Decay in western hemlock and fir in the Franklin River area British Columbia.

Bulliard 1780. Herbier de la France, 1: page 304 & plate 34. HYDNE hérisson. HYDNUM erinaceus.

Bulliard 1791. Histoire des champignons de la France, vol. 1, p. 304, plate 34, HYDNE hérisson. HYDNUM erinaceus.

Burdsall et alia 1978. Mycotaxon, 7(1): 1–9. Morphological and Mating System Studies of a New Taxon of Hericium (Aphyllophorales—Hericiaceae) from the Southern Appalachians.

Burova 1968 [as Бурова, Л.Г.]. Макромицеты парцелл елово-широколиственных лесов Подмосковья (на примере липо-ельника зеленчуково-волосистого [Macromycetes of spruce-deciduous forests parcels in Moscow region (using as an example of lime-spruce forest with Galeobdolon and Carex pilosa)]. Миколог.

(From Cybertruffle 2016. Not presently accessible.)

BVN 2009. Bow Valley Naturalist Newsletter, Fall.

CABI Index of Fungi, at http://www.cabi.org/publishing-products/online-information-resources/index-of-fungi/ [Link confirmed 17 March 2018.]

Callan 1998. Diseases of Populus in British Columbia: a diagnostic manual.

Campbell et alia 1950. Plant Disease Reporter, 34: 128–134. Notes on some wood-decaying fungi of Georgia.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Cardoso et alia 1992. Cryptogamia Botanica, 2: 395–404. Aphyllophorales of Peneda-Geres National Park (Portugal).

Cash 1953. The Plant Disease Reporter. Supplement 219. A Check List of Alaskan Fungi.

Chen 2002. Forest fungi phytogeography: Forest fungi phytogeography of China, North America, and Siberia and international quarantine of tree pathogens. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Chen 2003. Forest fungi phytogeography: Forest fungi phytogeography of China, North America, and Siberia and international quarantine of tree pathogens.

Chen et alia 2016. Persoonia, 37, 21–36. Global diversity and molecular systematics of Wrightoporia s.l. (Russulales, Basidiomycota).

(Paper included six Hericium species.)

Chevallier 1826. Flore générale des environs de Paris, 1: 270–279. Hydnum.

Colenso 1889. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 21: 43–80. A description of some newly-discovered cryptogamic plants; being a further contribution towards the making known the botany of New Zealand. Pages 79–80: Hydnum novae-zealandiae. [Spelling can sometimes be found amended to novae-zelandiae.]

Conkers 1935. Forest Insect Disease Survey. Canada Department Forestry, Annual District Report 14. (From Conners 1967. Not presently accessible.)

Conners 1967. Canada Department of Agriculture, Research Branch Publ. 1251. An Annotated Index of Plant Diseases in Canada and fungi recorded on plants in Alaska, Canada and Greenland.

Cooke 1871. Handbook of British Fungi, vol. 1, page 297. Hydnum coralloides, erinaceus & caput–medusae.

Cybertruffle’s Robigalia online. Observations of fungi and their associated organisms, at http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/robigalia/eng/index.htm [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Dai et alia 2009. Mycosystema, 29(1):1–21. A revised checklist of edible fungi in China.

Das & Sharma 2009–2010. Kavaka, (37–38): 17–19. Hericium cirrhatum (Pers.) Nikol.; A new record to Indian mycoflora.

Das et alia 2011. Cryptogamie, Mycologie, 32(3): 285–293. A new species of Hericium from Sikkim Himalaya (India).

Das et alia 2013. IMA Fungus, 4(2): 359–369. Two new species of hydnoid-fungi from India.

DAVFP Collections Database Pacific Forestry Centre’s Forest Pathology Herbarium, at http://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/herbarium [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Davidson et alia 1942. USDA Technical Bulletin 785, Fungi Causing Decay of Living Oaks in the Eastern United States and Their Cultural Identification.

Day & Nair ND. Host-Fungus Index of Wisconsin. http://www.uwgb.edu/biodiversity/resources/host-fungus-index/ [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Doğan & Öztürk 2006. Turkish Journal of Botany, 30: 193–207. Macrofungi and Their Distribution in Karaman Province, Turkey.

Doğan et alia 2005. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 37(2): 459–485. A Checklist of Aphyllophorales of Turkey.

Doll 1979. Feddes Repertorium, 90(1–2): 103–120. Die Verbreitung der gestielten Stachelpilze sowie das Vorkommen von Hericium, Creolophus cirrhatus, Spongipellis pachyodon, und Sistotrema confluens in Mecklenburg.

Domański et alia 1960. Monographiae Botanicae, 10(2): 150–237. Mycoflore Bieszczady Occidentales (Wetlina 1958).

Domański et alia 1960. Monographiae Botanicae, volume 15. Mikoflora Bieszadów Zachodnich. II. (Ustrzyki Górne, 1960).

Dudka et al. 2004. Fungi of the Crimean Peninsula. (Translated from Russian)

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

ECCF (European Council for Conservation of Fungi) 2001. Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. T-PVS 34: page 21. Datasheets of threatened mushrooms of Europe, candidates for listing in Appendix I of the Convention.

Ellett 1989. OSU, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, Special Circular 128, Ohio Plant Disease Index.

EMBL (European Molecular Biology Laboratory) 2019. Geographically tagged INSDC sequences. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/cndomv accessed via GBIF.org on 2019-02-20. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1941096220. See also entry at ENA (European Nucleotide Archive) https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/data/view/LC062612

[Links confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Eslyn 1962. Iowa Forest Science, 8: 263–276. Basidiomycetes and decay in silver maple stands of central Iowa.

Eslyn & Lombard 1983. Forest Product Journal, 33: 19–23. Decay in mine timbers. Part II. Basidiomycetes associated with decay of coal mine timbers.

Eslyn & Lombard 1984. Mycologia, 76: 548–550. Fungi associated with decayed wood in stored willow and cottonwood logs.

Filip et alia 1984. Plant Diseases, 68: 992–993. Substantial decay in Pacific silver fir caused by Hericium abietis.

Filip et alia 1995. Manual 9. Forest Disease, Ecology & Management in Oregon.

French 1989. California Plant Disease Host Index.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Gilbertson et alia 1974. University of Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin, 209: 1–48. Annotated check list and host index for Arizona wood-rotting fungi.

Ginns 1984. Mycotaxon, 20(1): 39–43. Hericium coralloides N. Amer. auct. H. americanum, and the European H. alpestre and H. coralloides.

Ginns 1985. Canadian Journal of Botany, 63(9): 1551–1563. Hericium in North America, cultural characteristics and mating behavior.

Ginns 1986. Research Board of Canadian Agriculture Publication 1813. Compendium of plant disease and decay fungi in Canada 1960–1980.

Gizhytska 1929 [as Гіжицька, З.К.]. Матеріяли до мікофльори України. Вісник Київського Ботанічного саду [Bulletin of the Kiev Botanic Garden] 10: 4–41.

(From Cybertruffle 2016. Not presently accessible.)

Glaeser & Smith 2010. Western Arborist, 32–46. Decay fungi of oaks and associated hardwoods for western arborists.

Glaeser & Smith 2013. Western Arborist, 40–51. Decay fungi of riparian trees in the Southwestern U.S.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) at http://www.gbif.org) [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Global Catalogue of Microorganisms, at http://gcm.wfcc.info [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Global Fungal Red List Initiative, at http://iucn.ekoo.se/iucn/species_view/120231 [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Grand 1985. North Carolina Agricultural Research Service Technical Bulletin, 240: 1–157. North Carolina Plant Disease Index. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Gray 1821. A Natural Arrangement of British plants, page 651: erinaceus; page 652: coralloides.

Groves 1981. Champignons comestibles et vénéneux du Canada.

Gulden & Stordal 1973. Blyttia, 31: 103–127. Om stilkete och kjukeformele piggsopper i Norge.

(From Koski-Kotiranta & Niemelä 1988. Not presently accessible.)

Hallenberg 1983. Mycotaxon, 18(1): 181–189. Hericium coralloides and H. alpestre (Basidiomycetes) in Europe.

Hallenberg et alia 2012. Mycological Progress, 12(2): 413–420. Species complexes in Hericium (Russulales, Agaricomycota) and a new species —Hericium rajchenbergii — from southern South America.

Haller 1768. Historia stirpium indigenarum Helvetiae, vol. 3, page 148. ECHINUS ramosus, aculeis parallelis.

Hampshire Biodiversity Partnership 2003. Hericium Tooth Fungi.

Hanlin 1966. Georgia Agricultural Experiment Station, Mimeo Series, n. s., 260: 1–30. Host index to the Basidiomycetes of Georgia.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Hansen & Vesterholt 2002. Rødlistede svampe i Storstrøms Amt 2001. Page 135: Creolophus cirrhatus; 138: Hericium erinaceum; 174: Hericium coralloides.

Harrison 1961. The Stipitate Hydnums of Nova Scotia.

Harrison 1973. Michigan Botanist, 12: 177–194. The Genus Hericium in North America.

Harrison 1984. Mycologia, 76: 1121–1123. Creolophus in North America.

Henderson 1981. Trial field key to TOOTHED FUNGI in the Pacific Northwest. (Pacific Northwest Key Council), at http://www.svims.ca [Link confirmed 19 Dec 2018.]

Heredia 1989. Acta Botánica Mexicana, 7: 1–18. Estudio de los hongos de la reserva de la biosfera el cielo, tamaulipas consideraciones sobre da distribucion y ecologia de alguinas especies.

(This was apparently a mis-citation by USDA.)

Hermansson 1997. Windahlia, 22: 67–79. Polyporaceae s. lat. and some other fungi in Pechora-Ilych Zapovednik, Russia. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Hibbett et alia 2000. Nature, 407: 506–508. Evolutionary instability of ectomycorrhizal symbioses in basidiomycetes.

Horst 2013. Westcott’s Plant Disease Handbook, pages 489–490. Hericium erinaceus.

Hubregtse 2018. Fungi in Australia. Part 4. Basidiomycota, Agaricomycotina – II, pages 226—227 & Part 9. Photographic guide to non-gilled fungi, page 20. Hericium coralloides.

Hyams 1900. North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Bulletin, 177: 27–77. Edible mushrooms of North Carolina.

Index Species Fungorum, accessed via CABI at http://www.speciesfungorum.org and Kew http://www.indexfungorum.org/Names/Names.asp [Links confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Jussieu ex Barrelier 1714. Plantae per Galliam Hispaniam et Italiam observatae iconibus aeneis exhibitae, page 118, fig. 1257. Fungus ramos. Abietin niveus

Karadelev 1993. Fungi Macedonici, I. Contribution to the knowledge of wood-destroying fungi in the Republic of Macedonia.

Karun & Sridhar 2016. Studies in Fungi, 1(1): 135–141. Two new records of hydnoid fungi from the Western Ghats of India.

Kaya 2009. Turkish Journal of Botany, 33: 429–437. Macrofungi of Huzurlu high plateau (Gaziantep-Turkey).

Karadzic 2006. Glasnik Sumarskog fakulteta, 93: 83–96. Contribution to the study of fungi in the genera Sparassis Fr. and Hericium Pers. in our forests Dragan,

Keizer 2008. De soorten van het leefgebiedenbeleid, 55–57, (Chapter 14) Echte Pruikzwam Hericium Erinaceum (Bull. ; Fr.) Pers.

Kew Gardens, at http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/plants-fungi/hericium-erinaceus-bearded-tooth [Link was 404 on 9 Dec 2018.]

Kimmey & Stevenson 1957. The Plant Disease Reporter, Supplement 247, 87–98. A Forest Disease Survey of Alaska.

Kobayashi 2007. Index of fungi inhabiting woody plants in Japan. Host, Distribution and Literature. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Koski-Kotiranta & Niemelä 1988. Karstenia, 27: 43–70. Hydnaceous fungi of the Hericiaceae, Auriscalpiaceae and Climacodontaceae in northwestern Europe.

Kreisel 1987. Pilzflora der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. Basidiomycetes (Gallert-, Hut- und Bauchpilze).

(From Koski-Kotiranta & Niemelä 1988. Not presently accessible.)

Kroeger & Berch 2017. British Columbia Ministry of the Environment, Technical Report, TR108. Macrofungus Species of British Columbia.

Kunca & Čiliak 2015. Czech Mycology, 67(1): 95–118. Abstracts of the International Symposium Fungi of Central European Old-Growth Forests, page 107. Ecology, incidence and indication value of Hericium erinaceus in Slovakia and the Western Carpathians.

Kunca & Čiliak 2017. Data in Brief, 12: 156–160. Dataset on records of Hericium erinaceus in Slovakia.

Kunca & Čiliak 2017. Fungal Ecology, 27(B): 189–192. Habitat preferences of Hericium erinaceus in Slovakia.

Kunca et alia 2018. Czech Mycology,70(2): 211–224. Fruitbody production of Hericium erinaceus and its distribution in Slovakia.

Kuo. Michael Kuo’s Mushroom Expert website: http://www.mushroomexpert.com [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Lacheva 2014. International Journal of Microbiology and Mycology, 2(3): 37–48. A case study on wood decaying macrofungi in the Southwestern slopes of Vasilyovska Mountain, Forebalkan, Bulgaria.

Lai K (2012). The National Checklist of Taiwan. Taiwan Biodiversity Information Facility (TaiBIF). (http://taibnet.sinica.edu.tw) [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Larsson & Larsson 2003. Mycologia, 95(6): 1037–1065. Phylogenetic relationships of russuloid basidiomycetes with emphasis on aphyllophoralean taxa.

Laursen & Seppelt 2009. Common Interior Alaska Cryptogams, pages 88–89. Hericium coralloides.

Lawrence & Hiratsuka 1972. Northern Forest Research Centre, Information Report NOR-X-27. Forest fungi collected in Yoho National Park, British Columbia.

Letellier 1826. Histoire et Description des Champignons. 112–113: Hericium caput medusae; 113–114: Hericium erinaceus; 114–115: Hericium coralloides.

Lindsey & Gilbertson 1978. Bibliotheca Mycologica, 63. Basidiomycetes that decay aspen in North America.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Lisiewska 2006. Acta Mycologica, 41(2): 241–252. Endangered macrofungi of selected nature reserves in Wielkopolska.

Lowe 1969. Canadian Forest Service, Victoria, Report B-X-32. Check list and host index of bacteria, fungi, and mistletoes of British Columbia.

Lowe 1977. Can. Forestry Service, Victoria. Report BC-X-32. (From Ginns 1986.]

Maas Geesteranus 1959. Persoonia, 1(1): 115–147. The stipitate Hydnums of the Netherlands — IV.

MacKay 1904. Proceedings and Transactions of the Nova Scotia Institute of Science, 12: 119–138. Fungi of Nova Scotia: a provisional list.

Magasi 1966. Canadian Forest Service, Fredericton. Report M—X—7. Index to the Forest Fungi of the Maritimes Region.

Mallams et alia 2010. USDA, Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 53. Decays of White, Grand, and Red Firs.

Maloy 1968. Plant Disease Reporter, 52: 489–492. Decay fungi in young grand fir. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Manaaki Whenus Landcare Research Databases — Ngā Harore o Aotearoa – New Zealand Fungi,

at

https://nzfungi2.landcareresearch.co.nz/default.aspx?selected=NameDetails&Action=Display&CancelScript=1&TabNum=0&NameId=B64DA912-C516-4B1F-8DCB-7C8915C1FF8D&StateId=&Sort=0

and

https://nzfungi2.landcareresearch.co.nz/default.aspx?selected=NameDetails&Action=Display&CancelScript=1&TabNum=0&NameId=7A6A7650-0256-4DB9-A9B5-9120C935A612&StateId=&Sort=0 [Links confirmed on 17 March 2019.]

Their link to http://194.203.77.76/LibriFungorum/Search.asp?ItemType=B was unresponsive.]

Maneval 1937. University of Missouri Studies, Sci. Ser. 12. A List of the Missouri Fungi.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Marchand 1975–1976. Champignons du Nord et du Midi. Vol. 3. (From Rastetter 1985; Not presently accessible.)

Martin & Gilbertson 1980. Mycotaxon, 10(2): 479–501. Synopsis of wood-rotting fungi on spruce in North America: III.

Massee 1892. British Fungus Flora, vol. 1. Pages 156–157: Hericium coralloides; 157: Hericium erinaceum; 157: Hericium caput-medusae.

McArthur 1966. Canadian Forest Research Laboratory, Calgary, Alberta. Information Report A-X-4. A list of specimens deposited in the mycological herbarium of the Forest Research Laboratory, Calgary, Alberta.

Merino Alcántara 2011. Micobotánica Jaén, 4 pages. Hericium alpestre. at http://www.micobotanicajaen.com/Revista/Articulos/DMerinoA/Aportaciones023/Hericium%20alpestre.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Merino Alcántara 2014. Micobotánica Jaén, 2 pages. Hericium erinaceus. At http://www.micobotanicajaen.com/Revista/Articulos/DMerinoA/Aportaciones023/HericiumErinaceus.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Michel 2007. Contribution à la connaissance de la fonge lignicole du site de Saint-Daumas, page 24.

Micheli 1729. Nova plantarum genera juxta Tournafortii methodum disposita, page 122. Agaricum esculentum, album, cespitosum, multifidum & denticulatum, denticulis asperis.

Miller 1935. Mycologia, 27(4): 357–373. The Hydnaceae of Iowa. IV. The Genera Steccherinum, Auriscalpium, Hericium, Dentinum and Calodon.

Miller et alia 2006. Mycologia, 98(6): 960–970. Perspectives in the new Russulales.

Mir et alia 2017. Micobotánica-Jaén, 12(2): ONLINE. Aportación al Catálogo Micológico de las Illes Balears. Menorca, III. See at http://www.micobotanicajaen.com/Revista/Articulos/JLMelis/MenorcaIII/APORTACION%20AL%20CATALOGO%20MICOLOGICO%20III%20v2r.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Molina et alia 1993. USDA, Forest Service, General Technical Report PNW-GTR-309. Biology, Ecology, and Social Aspects of Wild Edible Mushrooms in the Forests of the Pacific Northwest: A Preface to Managing Commercial Harvest.

Molnar 1956. Annual Report of the Forest Insect and Disease Survey, 1956, 87–91. Province of British Columbia. Forest Disease Survey.

Monica 2014. http://www.monicanetwork.dxnitaly.com [Link was 404 on 9 Dec 2018.] [also www.retestatic.it/download.php?f=307416.pdf (Link confirmed 19 Dec 2018.)]

Morel Mushroom Hunting Club (i.e. Chris Matherly), at www.morelmushroomhunting.com/herricium_coralloides_var_rosea.htm [Link was 404 on 9 Dec 2018. Possibly moved to paid-access only?] [As herricium [sic] coralloides var. rosea.]

Mori et alia 2008. Phytotherapy Research, 23(3): 367–372. Improving Effects of the Mushroom Yamabushitake, Hericium erinaceus, on Mild Cognitive Impairment; A Double blind Placebo controlled Clinical Trial.

And also in

Mori et alia 2008. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 31 (9): 1727–1732. Nerve Growth Factor Inducing Activity of Hericium erinaceus in 1321N1 Human Astrocytoma Cells.

Mycobank at http://www.mycobank.org/name/Hericium%20erinaceum&Lang=Eng) [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Mycology.su (The Red Book of Russia Plants), at https://mycology.su/category/fungi/basidiomycota/agaricomycetes/russulales/hericiaceae/hericium Род: Гериций (Hericium) [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Mycoweb, at http://www.mykoweb.com [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Nakasone 1996. in McMinn et alia USDA, Forest Service, General Technical Report, GTR-SE94, Biodiversity and Coarse woody Debris in Southern Forests. pages 35–42: Diversity of Lignicolous Basidiomycetes in Coarse Woody Debris.

Nanagulian & Senn-Irlet 2002. Some Dates [sic] About Distribution and Conservation of Threatened Mushrooms in Armenia.

Natural Resources Canada 2015. Yellow pitted rot. https://tidcf.nrcan.gc.ca/en/diseases/factsheet/1000025 [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Nikolajeva 1961. Flora plantarum cryptogamarum URSS. Fungi. Familia Hydnaceae, 6(2): 1–432. Page 238: Hericium schestunovii.

(Cited by many references; book is not presently accessible.) Николаева Т. Л. Флора споровых растений СССР. Том VI. Ежовиковые грибы. Грибы (2). — М. – Л.: Издательство Академии наук СССР, 1961. — 433 с; NIKOLAEVA, Taisiya Lvovna (1961). In: SAVIČ V. (ed.), Флора споровых растений СССР [Flora plantarum cryptogamarum URSS 6. Fungi 2. Familia Hydnaceae]. 6(2): 1–432 . Moscow; Leningrad

Nordin 1954. Canadian Journal of Botany, 32(1): 221–258. Studies in Forest Pathology. XIII. Decay in Sugar Maple in the Otttowa-Huron and Algoma Extension Forest Region of Ontario.

Nuß 1973. Westfälische Pilzbriefe, 9: 130–134. Über die Verbreitung des Alpen-Stachelbartes (Hericium coralloides) in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Oudemans 1919–1924. Enumeratio systematica Fungorum.

Ostry et alia 2011. USDA, Forest Service. GTR-79. Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions.

Otani (ex Ito) 1957. Journal of Japanese Botany [Shokubutsu Kenkyu Zasshi], 32(10): 303–306. On a new species of Hericium found in Japan.

Pallua et alia 2012. Analyst, 137: 1584–1595. Morphological and tissue characterization of the medicinal fungus Hericium coralloides by a structural and molecular imaging platform.

Parris 1959. Mississippi State University, Botany Department Miscellaneous Publication 1. A revised host index of Mississippi plant diseases.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Park et alia 2014. Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, 14(4): 816–821. Molecular Identification of Asian Isolates of Medicinal Mushroom, Hericium erinaceum, by Phylogenetic Analysis of Nuclear ITS rDNA.

Paulet 1793. Traite des champignons, vol. 2, pages 424–428.

Pegler 2003. Mycologist, 17(3): 120–121. Useful fungi of the world: the monkey head fungus.

Persoon 1794. (In Roemer’s) Neues Magazin für die Botanik, pages 151 & 153, page 153: erinaceus.

Persoon 1797. Commentatio de Fungis Clavaeformibus, page 27: erinaceus.

Persoon 1801. Synopsis Methodica Fungorum, page 560: erinaceus.

Persoon 1818. Traite sur les Champignons Comestibles. (Typo erinaceum appears on page 251).

Persoon 1825. Mycologia Europaea, volume 2, page 153: erinaceus.

Pilley & Trieselmann 1969. Canadian Forestry Service, Sault Ste Marie. Report O-X-108. A synoptic catalogue of cryptogams deposited in the Ontario region herbarium II. Basidiomycetes.

Pollini 1824. Flora Veronensis quam in prodromum flora, vol. 3. pages 595–597.

Pomerleau 1980. Flore des champignons au Québec et régions limitrophes. (From Ginns 1986. Not presently accessible.)

Preston & Dosdall 1955. USDA, Plant Disease Epidemiology & Identification Section, Spec. Publ. 8. Minnesota Plant Diseases.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Rastetter 1983. Mitteilungen des Badischen Landesvereins für Naturkunde und Naturschutz, 2: 161–188. Fünfter Beitrag zur Pilzflora des Oberelsaß.

Rea 1922. British Basidiomycetae: a handbook to the larger British Fungi.

Red Book of the Novosibirsk region 2018. [Красная книга Новосибирской области 2018]

(From Mycology.su. Not presently accessible.)

Red Book of Russia. Plants; Красная Книга России, at http://biodat.ru/db/rbp/rb.php?src=1&vid=527 [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Roger’s mushrooms, at http://www.rogersmushrooms.com [Server not responding in Nov. 2018 and Jan. 2019. Apparently now exists as a phone app.]

Rupcic et alia 2018. International Journal of Molecular Science, 2018, 19, 740, 12 pages. Two New Cyathane Diterpenoids from Mycelial Cultures of the Medicinal Mushroom Hericium erinaceus and the Rare Species, Hericium flagellum.

Safonov 1999 [as Сафонов, М.А.]. Трутовые грибы (Polyporaceae s.lato) лесов Оренбургской области [Polyporous fungi (Polyporaceae s. lato) from forests of Orenburg oblast]. Микология и Фитопатология [Mycology & Phytopathology] 33(2): 75–80. (From Cybertruffle 2016. Not presently accessible.)

Safonov 2014. European Researcher, 83(9–2): 1671–1676. Wood-destroying Basidiomycetes found on the elder woods in the South Urals (Orenburg Oblast, Russia).

Schmid-Heckel 1988. Forschungsberichte Nationalpark Berchtesgaden, 15: 1–136. Pilze in den Berchtesgadener Alpen.

Shaw 1973. Washington Agricultural Experiment Station, Bulletin 756. Host fungus index for the Pacific Northwest — 1. Hosts. (From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Sikora & Neubauer 2015. Chrońmy Przyrodę Ojczystą, 71(5): 368–379. Nowe stanowiska i występowanie soplówki jeżowatej. Hericium erinaceus w Polsce.

Siller et alia 2005. Studia Botanica Hungarica, 36: 131–163. Hungarian Distribution of the Legally Protected Macrofungi Species.

Singh et alia 2017. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology, 7(3): 208–226. Wild edible mushrooms from high elevations in the Garhwal Himalaya—II.

Singh & Das 2019. Nova Hedwigia, 108(3–4): 505–515. Hericium rajendrae sp. nov. (Hericiaceae, Russulales): an edible mushroom from Indian Himalaya.

Slippers et alia 2000. Mycologia 92(5): 955–963. Relationships among Amylostereum species associated with siricid woodwasps inferred from mitochondrial ribosomal DNA sequences.

[Included Hericium ramosum only as an outlier; gave no indication as to its point of origin.]

Snowarski 1997–2019. Grzyby Polski: Creolophus cirrhatus: https://www.grzyby.pl/gatunki/Creolophus_cirrhatus.htm, Hericium coralloides: https://www.grzyby.pl/gatunki/Hericium_coralloides.htm; Hericium erinaceus: https://www.grzyby.pl/gatunki/Hericium_erinaceum.htm; Hericium flagellum: https://www.grzyby.pl/gatunki/Hericium_flagellum.htm.

Sokół et alia 2016. Acta Mycology, 50(2): article 1069. 18-pages. Biology, cultivation and medicinal functions of the mushroom Hericium erinaceum.

Stalpers 1992. Persoonia, 14(4): 537–541. Albatrellus and the Hericiaceae.

Stalpers 1996. Studies in Mycology, 40. The Aphyllophoraceous fungi. — II. Keys to the species of the Hericiales.

Stasińska 1999. Acta Mycologica, 34(1): 125–168. Macromycetes in forest communities of the Insko Landscape Park (NW Poland).

Sterbeeck 1675. Theatrum Fungorum oft Tooneel der Campernoelien, pages 254–255. [as = Cornu cervi calcinatum.]

Stevenson 1886. British Fungi, vol. 2. 239–240: Hericium coralloides; 240: Hericium erinaceum; 240: Hericium caput-medusae.

Stevenson 2016. Wild Edible Food. https://www.ediblewildfood.com/blog/2016/10/lions-mane-edible-and-medicinal-fungi/ [Link confirmed 12 April 2019.]

Sultana & Qreshi 2007. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 39 (7): 2629–2649. Check List of Basidiomycetes (Aphyllo. and Phragmo.) of Kaghan Valley-11.

Swiecki & Bernhardt 2006. A Field Guide to Insects and Diseases of California Oaks, (USDA PSW GTR-197), pp. 99–101. Hedgehog mushroom, Hericium erinaceus f. erinaceus.

Tai 1979. Sylloge Fungorum Sinicorum.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Tanchaud 2011. Hericium cirrhatum, at www.mycocharentes.fr/pdf1/82%20115%201%20.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Tanchaud 2015. Hericium clathroides, at https://www.mycocharentes.fr/pdf1/1747.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Tanchaud 2018. Hericium cirrhatum, at https://www.mycocharentes.fr/pdf1/2206.pdf [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Teng 1996. Fungi of China.

(From Cybertruffle 2016 & USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Thind & Khara 1975. Indian Phytopathology, 28: 57–65. The Hydnaceae of the North Western Himalayas–II.

(From Karun & Sridhar 2016. Not presently accessible.)

Thomas & Podmore 1953. Canadian Journal of Botany, 31: 675–697. Studies in Forest Pathology. XI. Decay in Black Cottonwood in the Middle Fraser Region, British Columbia.

Thongbai et alia 2015. Mycological Progress, 14:91 (23 pages) Review: Hericium erinaceus, an amazing medicinal mushroom.

Tidwell 1990. Index of Diseases and Microorganisms Associated with Eucalyptus in California.

(From USDA ARS GRIN. Not presently accessible.)

Tortič 1998. Folia Cryptogamica Estonica, 33: 139—146. An attempt to a list of indicator fungi (Aphyllophorales) for old forests of beech and fir in former Yugoslavia.

Trattinnick 1805. Fungi Austriaci, 191–196. XXV. Hydnum erinaceus Bull.

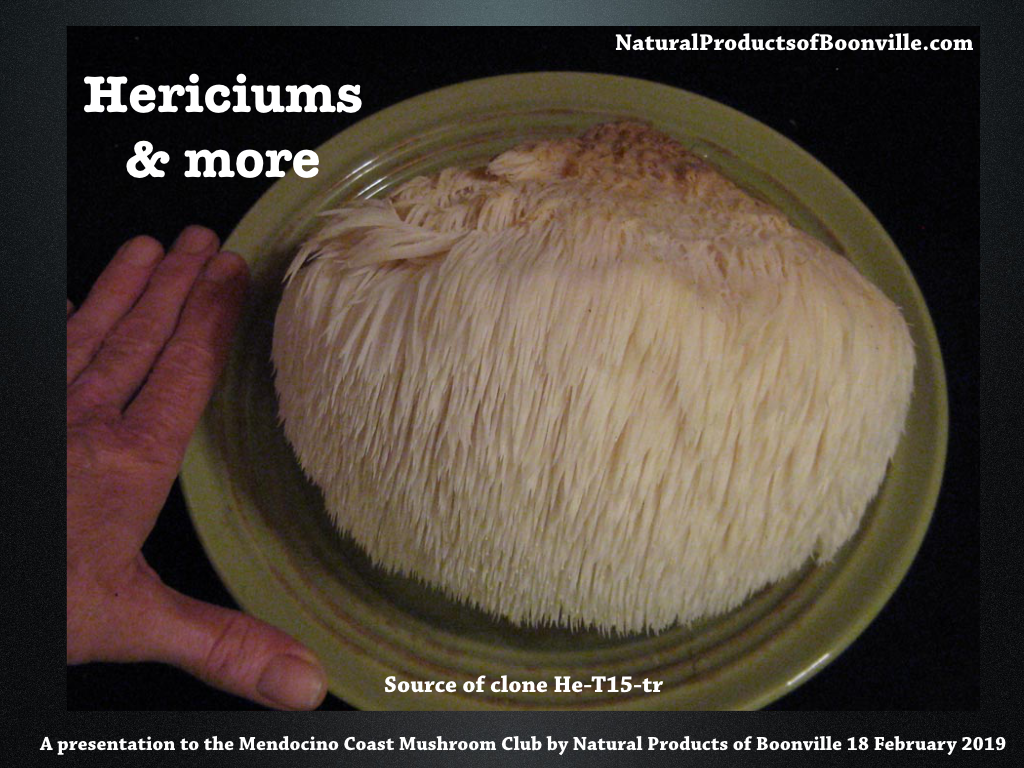

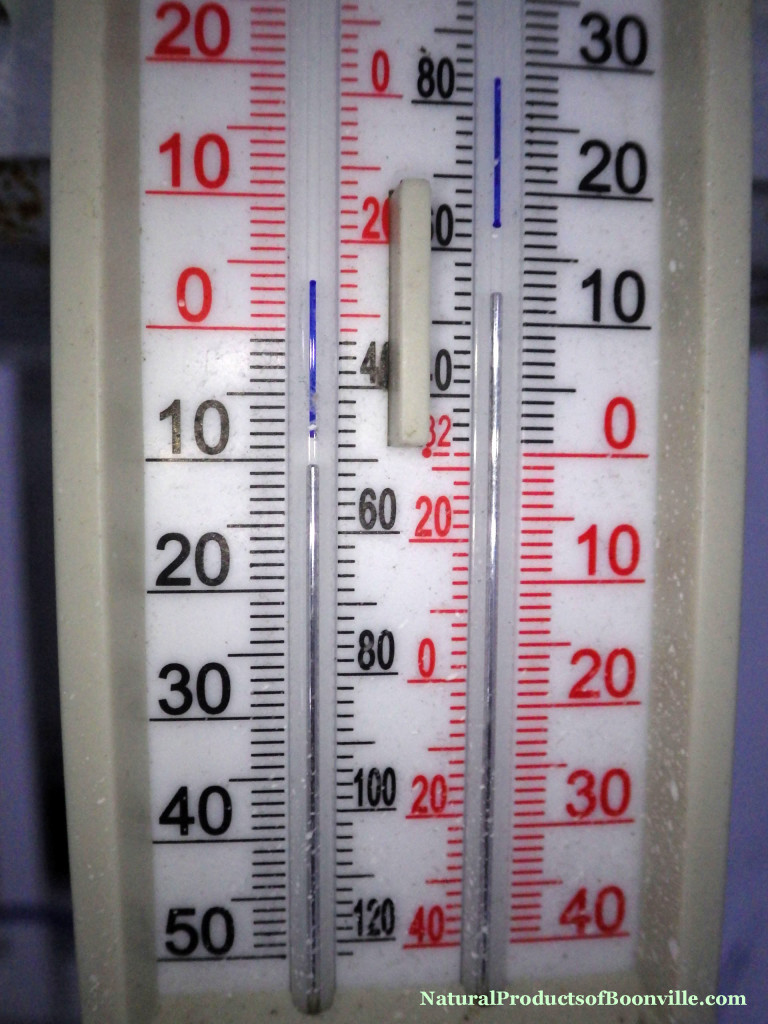

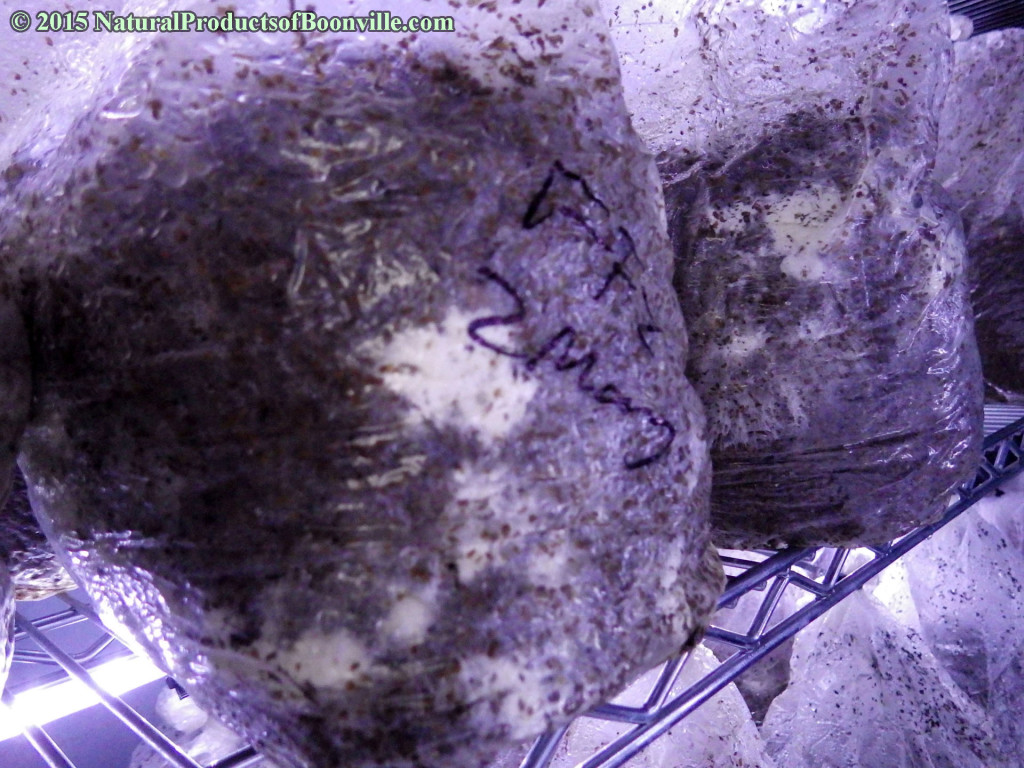

Trout 2004–2015. “Local observation” was for environs of Boonville, Philo & Yorkville, in Anderson Valley, Mendocino County, California.

Turland et alia (eds.) 2018: International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017. Regnum Vegetabile 159.

Urban 2015. Czech Mycology, 67(1): 95–118. Abstracts of the International Symposium Fungi of Central European Old-Growth Forests, page 117. Substrate specificity does matter — macro-fungal succession on coarse woody debris in an old-growth oak forest.

USDA ARS GRIN Fungal Databases. Information gleaned via individual species name searches at https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/nomen/new_frameNomenclatureReport.cfm [Link confirmed 21 Feb 2019.]

Van Hook 1922. Proceedings of Indiana Academy of Science, 1921: 143–148. Indiana Fungi — VI.

Varstvo gozdov / Boletus informaticus, at http://www.zdravgozd.si [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Varstvo gozdov / Boletus informaticus, at http://www.zdravgozd.si [Link confirmed 17 March 2019.]

Volk et alia 1994. Mycotaxon, 52(1): 1–46. Checklist and Host Index of Wood-Inhabiting Fungi of Alaska

Wald et alia 2004. Mycological Research, 108(12): 1447–1457. Interspecific interactions between the rare tooth fungi, Creolophus cirrhatus, Hericium erinaceus and H. coralloides, and other wood decay species in agar and wood.

Wehmeyer 1950. Fungi of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Yurchenko 2002. Mycena, 2(1): 31–68. Non-poroid aphyllophoraceous fungi proposed to the third edition of the Red Data Book of Belarus. [Hericium coralloides: pages 47—50.]

Zervakis et alia 1998. Mycotaxon, 66: 273–336. A check-list of the Greek macrofungi including hosts and biogeographic distribution: I. Basidiomycotina.

Ziller 1957. Fungi of British Columbia deposited in the herbarium of the Forest Biology Laboratory, Victoria, B.C., Canada. (From Conners 1967. Not presently accessible.)

Ziller 1961. Interim Report. Forest Entomology and Pathology Laboratory, Victoria, BC. A List of Pathogens on Pinus, Populus, and Quercus in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory.

Zutshi & Gupta 2013. Journal of Mycopathological Research, 51: 361–363. Occurrence and characterization of Hericium coralloides: a rare wild edible mushroom from Doda region of J & K, India.

(Cited by Karun & Sridhar 2016; paper was unavailable. Could only access its abstract.)

Sridhar 2016; paper was unavailable. Could only access its abstract.)