We’ve been so busy it is challenging to keep up with uploading videos.

This was the view inside on the 3rd. Thanks for everyone’s interest in our mushrooms! We hope to see you Saturday at the Farmer’s Market in Ukiah or locally another day.

We’ve been so busy it is challenging to keep up with uploading videos.

This was the view inside on the 3rd. Thanks for everyone’s interest in our mushrooms! We hope to see you Saturday at the Farmer’s Market in Ukiah or locally another day.

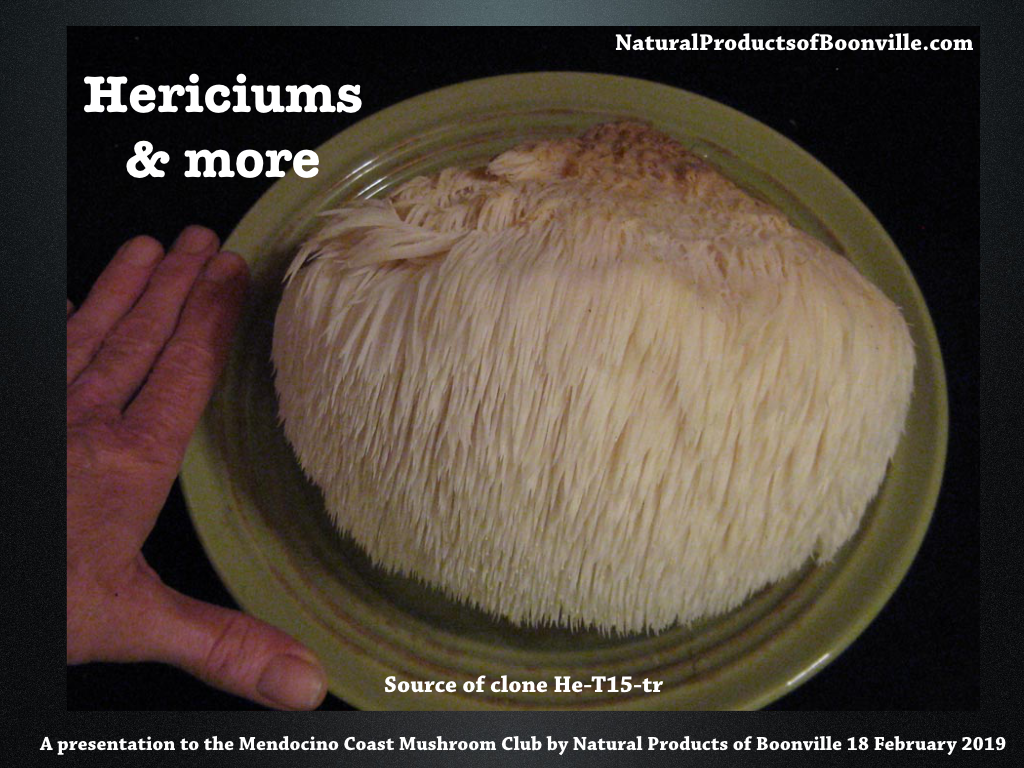

A slideshow and talk was recently given to the Mendocino Coast Mushroom Club. It was a lot of fun that included meeting a bunch of really nice mushroom people!

I had hoped to load that slideshow to the website but encountered some technical difficulties. It was instead turned into a ~157mb PDF that can be accessed HERE. The only slide that did not import was the video above.

Comments about our cultivated Lion’s mane mushrooms

Why do we only sell cultivated Hericium?

Why not add some *wild* harvested Hericium?

It is certainly possible to harvest the Hericium species and many other mushrooms from the wild. Both of us have been avid foragers of wild mushrooms for some years now, to be part of our own diet, and we consume a rather substantial quantity of wild Hericium species every year, but we sell only cultivated mushrooms.

There are many benefits of mushroom cultivation.

A few of those include:

1) a predictable supply that is not based on lucky weather, seasonally limited fruiting periods, and the timing of visitation all coinciding productively,

2) the ability to harvest only the highest-quality mushrooms at their peak,

3) knowing that they are free from molds,

4) the ability to prevent excessive moisture content (a frequent challenge with wild lion’s mane especially when large),

5) the production of fungal bodies that are clean (rather than containing forest debris, and many tiny beetles , fungus gnats, their larvae, and mites, often inside of the mushroom’s tissues, as is quite common with wild-collected lion’s mane),

6) much greater personal safety during harvesting; compared to climbing or otherwise recovering fruiting bodies from a rotting tree (& it completely avoids the uniquely unpleasant but harmless experience of “catching” a large falling lion’s mane with one’s forehead),

AND

7) there is the added benefit of control over the ingredients of the media; ensuring the least possible risk of any type of heavy metal accumulation.

That last point is an important concern about which many people appear to be aware.

We commonly associate heavy metals with industrial pollution and can forget that potentially toxic elements such as lead, mercury, cadmium, nickel and arsenic are not uncommonly natural and normal minor components of rocks and soil. Many of the edible mushroom species appear to have the ability to accumulate one or more of these metals IF they are present and bioavailable in their surroundings.

Cultivation permits the grower to know, within reason, exactly what is contained in their growing media and minimize that risk. In the EU, maximum permissible levels of heavy metals have been established for both wild and cultivated mushroom species that are sold to the public. The USA lacks regulation in this particular area.

How mushroom cultivation works (a more detailed pictorial will be added here in the future):

All media (whether liquid culture, agar, grain or sawdust) is first cooked in a pressure cooker in an attempt to kill any potential contaminant prior to the inoculation. The inoculation work is performed in front of a hepafiltered flowhood that temporarily creates a clean, almost sterile, working space as the resulting filtered air-flow is free from microbes and mold spores.

Cultures of the edible mushroom species are far more often produced by cloning than from spores. The reason is simple; spores produce a broad range of individuals with different performances and yields. A commercial mushroom producer needs to select for only the most vigorous and productive of those in order to be a successful farmer. Once a good performing clone has been identified and proven by growing it out through the entire fruiting process, future propagation focuses on inoculations using that same clone line. Most, perhaps all, professional cultivators keep an eye out for unusually nice fruiting bodies that might provide a lineage of good production for them.

Clones are created by taking a small piece of tissue from inside of a living mushroom and transferring it to a sterile culture medium of some sort.

Commercial sources exist for Hericium erinaceus, and up to three other species (H. americanum, H. clathroides & H. coralloides). They are variously available as mycelial cultures on agar, in petri dishes or slants, and in liquid culture, as well as grain spawn, sawdust spawn intended for plugging logs, hardwood dowels colonized with mycelium, and sometimes even precolonized on sawdust cakes ready-to-fruit.

The growth of cultures that are intended for production are often begun on either agar in a petri dish or in water in a jar that has a filter disk for a lid — either one containing a low concentration of a source of sugar such as dextrose or light malt extract.

This can then be repeated once the colonization has taken place and small portions of the mycelium can be used to inoculate additional plates of agar or liquid culture or at some point either can be transferred onto grain.

Each jar of colonized grain can potentially then be used to inoculate more jars of grain. The endpoint for those jars of grain is that they are eventually used to inoculate a number of bags of sawdust that have been supplemented with wheat bran and a mixture of gypsum and oyster shell.

After the bags are inoculated, they get to luxuriate in the cool, moist, protected environment of their fruiting chamber (an insulated shipping container with filtered air and good pre-conditioned ventilation). As soon as the bags are colonized, small cuts are made in a couple of spots to permit the fruit to form on the outside of the bag.

The fruit tends to naturally occur most often on a vertical surface, or even under a negative incline, rather than on top of a horizontal surface. This particular run pictured below is evaluating the yield from a top fruiting arrangement.

A short tour of the Hericium fruiting chamber:

Our favorite time to harvest is when the teeth have just started. The texture is nice, the taste is mildly almost sweet and the shelf-life is longer.